Coccidiosis in calves

What is coccidiosis?

Coccidiosis is a disease of the intestinal tract caused by single celled intracellular parasites of the genus Eimeria. It affects several different species, both farmed and wild, with young stock such as lambs and calves being at highest risk of disease.1

In studies, 100% of sheep housing and 60% of pastures were contaminated with the pathogenic sheep species and another showed up to 100% prevalence in beef and dairy herds.2

There are over 20 different species of coccidia in cattle and sheep which are host-specific, with no cross infection between different host species, but in calves three cause disease:

- Eimeria zuernii

- Eimeria bovis

- Eimeria alabamensis

It is important to understand when faecal egg testing: a single high oocyst count does not in itself confirm coccidiosis and further investigation to identify the species of Eimeria is often necessary.

Coccidial infections are not always obvious or easy to see. Despite this, the parasite is very prevalent in the environment and nearly all cattle and sheep have some coccicial oocysts in their faeces.2 It is also very difficult to destroy (even with disinfectants) and can survive in the environment for up to two years: this means it is almost impossible to eliminate coccidia at farm level.

How do calves become infected with coccidiosis?

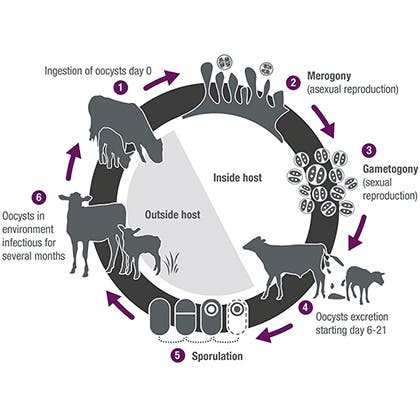

Contaminated water and feed troughs, and the skin of dams’ udders are common routes for the spread of coccidiosis and infection is by the faecal-oral route: once oocysts (eggs) are passed out they can be eaten by the same or new animal. As a rule, whilst adult animals may be the initial source of infection, heavy contamination comes from naïve calves themselves which, after contracting the initial infection, can go on to excrete millions of oocysts into their environment. Subsequent groups of naïve young animals then entering that same environment are exposed to a far higher challenge and are far more likely to suffer significant gut damage, production losses and disease.

How the damage is done

As it progresses through its life cycle this parasite reproduces within the cells that line the gut causing the cells to rupture and damaging the villi (finger like projections that increase the surface of the gut to maximise absorption of nutrients).

This damage reduces the amount of nutrients absorbed, causing ill health, poor growth rates and leaving them susceptible to other diseases. However, the obvious signs of disease (such as diarrhoea) do not appear until after a significant level of damage has already happened, leading to reduced growth rate and economic loss3.

The consequences of this lifecycle being allowed to continue can be devastating. A single ingested oocyst can lead to the destruction of 32 million intestinal cells (and result in serious gut damage) and lead to the production of a further 16 million oocysts to further contaminate the environment2.

Immunity to coccidiosis

Young animals initially acquire a degree of immunity against coccidiosis from antibodies absorbed from colostrum when born. As this initial protection wanes, calves become particularly susceptible to infection - most commonly between 3 weeks and 6 months of age.

Symptoms of coccidiosis

As a general rule, animals with high burdens of infection or low levels of resistance – especially young animals – will display clinical signs.

The clinical signs of coccidiosis are:

- Loss of appetite

- Diarrhoea (from green and slimy to bloody)

- Dehydration

- Straining – which can lead to rectal prolapse

- Abdominal pain

- Wasting

- Death

The damage to the gut allows for secondary bacterial infections to occur.

Cases of subclinical coccidiosis are also very common and whilst, often going unnoticed, they account for as much as 61% of total losses related to coccidiosis4.

Diagnosing coccidiosis in calves

Coccidiosis should be suspected in animals of the right age group showing the typical clinical signs and confirmed by analysis of faecal samples. It is important to understand though that when faecal egg testing, a single high oocyst count does not in itself confirm coccidiosis and further investigation to identify the species of Eimeria is often necessary.

Always seek veterinary advice and have a confirmed diagnosis of coccidiosis before recommending a treatment.

Risk factors that trigger coccidiosis

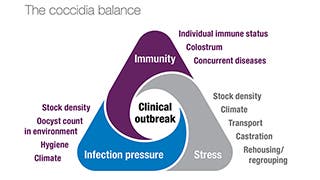

So, whilst most animals have some coccidia not all farms see clinical disease. The outcome of infection is a balance between the infection pressure, immunity and various stress factors that may lower the animal’s ability to cope with infection. These range from overstocking and re-housing to poor hygiene and bad weather.

Treatment of coccidiosis in calves

When to treat can be a matter of knowing the farm’s history and when challenges are expected. In general, calves are at most risk from 3 weeks – 6 months of age, and with indoor rearing systems, treatment can be given one week before the expected disease outbreak, or two weeks after a significant stress.

What are the treatment options?

In many circumstances, hygiene measures alone will not adequately control the level of oocysts in the environment. And, as noted previously, with oocyst excretion from adults at a very low level, it is infections in lambs and calves that are the source of the high levels of oocysts that can lead to clinical disease and production losses.

In this case, appropriate medication can be targeted at young stock that have been exposed to a significant challenge, thus preventing disease while allowing natural immunity to develop. Treatment options for young stock include sulphonamides (antibiotics, by injection), decoquinate (in feed) or the triazinone derivatives diclazuril and toltrazuril (oral drenches). Individuals with clinical signs of disease may also need other supportive treatments until the gut damage has had time to heal.

Whilst in-feed preparations rely on all animals eating enough to get an effective dose, oral drenches are generally the most convenient way of ensuring that each animal receives the correct dose at the correct time, allowing enough exposure to stimulate immunity before removing the parasites.

Management of coccidiosis

Good management of coccidia means helping animals to avoid disease and production losses whilst ensuring youngstock get enough exposure to the parasite to develop immunity.

Limiting the build-up of oocysts in the environment will help reduce infection pressure and the chances of disease. This can be done by taking simple measures such as:

- Providing dry, clean bedding.

- Avoiding overstocking and stress.

- Keeping youngstock in tight age groups (ideally no more than 2 weeks difference across the group).

- Keeping feed and water troughs clean and clear of faecal contamination.

- For housed animals, thorough cleaning of premises between batches.

- Turning young animals out onto fresh pasture, not previously used that season by other lambs or calves.

Managing worms in cattle

Worm burdens can cause productivity losses and affect growth rates in youngstock.

Liver fluke in cattle

Find out why liver fluke in cattle is a growing threat, management strategies and treatment options.

- Taylor, M. A., and J. Catchpole, 1994: Coccidiosis of domestic ruminants. Appl. Parasitol. 35, 73-86.

- Janssen Technical Brochure 2009

- Efficacy of diclazuril against naturally acquired Eimeria infections in suckling beef calves and economic benefits of treatment. J Agneessens, L Goossens, P Veys and D Gradwell. Cattle Practice, The Journal of the British Cattle Veterinary Association, 2005, vol. 13, p231-234

- Daugschies, A, Agneessens J, Goossens L, Mengel H, Veys P. The effect of a metaphylactic treatment with diclazuril on the oocyst excretion and growth performance of calves exposed to a natural Eimeria infection. Veterinary Parasitology 149 (2007) 199–206